IOMC Controversy!

A new controversy arose yesterday at the much-plagued International Outdoor Musical Chairs Competition. After being ousted in what has been described as one of the most closely contested two-chair semi-finals ever witnessed in an IOMC event, Teodor Karpinski accused one of his opponents, Jibu Abaya of Sudan, of steroid use. Karpinski also claimed the IOMC-licensed judge from Norway, Holge Stodborg, was biased in favor of the Norwegian finalist Hodor Stodborg.

Even before the competition started allegations were made that several IOMC committee members had accepted bribes to vote in favor of holding the event at Loodberry, CT. Each of the IOMC members denied being influenced by the "token financial gifts" provided by the Loodberry Chamber of Commerce. Given that no world class musical chairs competition had ever taken place in Loodberry before, IOMC critics voiced their skepticism.

The criticism grew louder when it was discovered that the musical chairs pitch was nothing more than a not-too-recently mowed cow pasture. "It's disgusting," said U.S. musical chair champion Morty Praeger. "There's cow poo everywhere. At least I think it's cow poo." Other contestants complained about the quality of the pitch. "We don't mind if the pitch is uneven," stated French contender Lucien De Noeuf. "That's why we play outdoors, for a challenge that cannot be matched by indoor musical chairs. But this pitch is dotted with rabbit burrows. At least I think they're rabbit burrows."

Despite the allegations and the complaints, the event took place as scheduled. Despite the delays to remove injured players and to clean bovine feces from the specially designed musical chair shoes, the competition was fast and furious. By yesterday, all but three of the 136 international competitors had been eliminated.

Many competitors and fans suggest Karpinski's allegations are groundless, nothing more than sour grapes. There appears to be little evidence to support the claim that Abaya, the 103 pound Sudanese contender, has used illegal steroids. However, many international musical chairs observers have quietly voiced concerns about a possible relationship between the Norwegian champion and the Norwegian judge. "There are just too many coincidences," said an anonymous Canadian official. "They have the same last name, they share a motel room when they travel, and according to their passports they both reside in the same house in Puderborg. It's not natural."

The competition has been suspended until Karpinski's allegations can be fully investigated and the results covered up. For now, there is nothing to see in the quiet town of Loodberry but the unhappy faces of musical chairs fans who've crossed the globe to observe this competition. Nothing except the two isolated chairs on the IOMC pitch.

Shadows Cannot Be Stolen

They took everything. The flat screen television, the DVD player, the stereo, the computer. They took the camera equipment, the binoculars, the CD collection, and all the DVDs except the musicals. They took both guitars and they took the violin that had belonged to his grandfather.

He'd come back from the wake and found their...his...no, their apartment had been burgled. "Theives read the obituaries," the police officer told him. "That lets them know when the viewing and funeral are held. They know you'll be out of the house then."

It took a while for him to fall asleep that night. He slept until the sun woke him. He laid in bed, alone in bed, thinking that he'd forgotten again to set the coffee machine so the coffee would be ready when he awoke. That had always been Philip's chore; it was his coffee machine. His television and DVD player that had been stolen. His computer. Their apartment.

In a few hours he'd get up, find the strength to shower, put on his dark suit, and go watch Philip's casket lowered into the ground. Later he'd call the insurance company to file a theft claim.

But for now it was enough to lay in bed and watch the shadow of the plant outside the window sway in the wind. He'd lost Philip. They'd taken his possessions. But that shadow would be there in the morning. Not everything in the world is as permanent as shadows.

Goat Dance

She remembers the day...the exact moment...she awoke. She was fifteen and she'd come home from shopping with her friends. She'd bought ring, a cheap gaudy ring, an absurd ring with a cloudy, misshapen stone that looked to her like the head of a goat. She'd bought it simply because it pleased her. Because it made her smile. Because it spoke to something inside her, spoke to some cloudy, misshapen, goat-headed aspect of her being.

"You don't

like that," her mother said. But yes, she did. "You're not going to

wear it." But yes, she was. "Your friends will make fun of you," her mother said. And yes, they had.

And it bothered her. But not enough to give up the ring. And that was the moment, that was when she awoke. She realized a thing could be cloudy and still provide clarity, a thing could be seen as misshapen and still be perfectly formed. She awoke and determined never again to go back to sleep. She would live her life the way a goat dances, gamboling and leaping, assured of her balance.

Others would understand. Or fail to understand. Or be cruel. Or be proud. She'd continue to care about those others, and she'd smile or weep or rage or laugh at what they'd say. But that ring would always make her smile.

Different World

It's too late for me. Not like these young guys I see today. They just come right out with it. "I'm gay." Hell, they even call themselves queer. That was the worse thing they could call you, used to be, queer. Or faggot. They probably call themselves that too. I just called myself a bachelor. Lifelong bachelor.

Pisses me off, sometimes, they got it so easy. Makes me proud, too, though. Takes balls, call yourself queer. Call yourself queer, takes the sting out of it if somebody else call you that. I still can't do it, though. Couldn't call myself that.

They got parades now. Only parade I was ever in was after the war. World War Two. Had a little parade for veterans back home in Keokuk. I was in the Marines. First Marine Raider Battalion. Took a couple rounds...one in the hip, one in the thigh...on Tulagi, August, 1942. Little piece of shit island, Tulagi. Only a couple miles long, maybe seven or eight hundred yards wide. Don't know what the fuck we doing there. Except killing Japs.

We can't call 'em Japs no more. That's the world, now. We can say queer but we can't say Jap. It's better this way.

It'd be nice to be young again.

Umbra

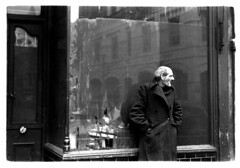

I threw away all the photographs of us together. All but this one.

"We can split the photos," she said. "You can keep them," I told her. But she left half of them anyway. I suppose she thought she was being kind. I suppose she thought I'd want to look at us together when we were happy. Does an amputee want to look at photographs of his healthy leg before it became gangrenous? No, he just wants the stump to heal, he just wants it to stop leaking pus.

I threw the photographs away. But I kept this one. I can look at our shadows together. This is what I see every day now, the absence of her. The space she's left behind. A flat and faceless form created because she blocked out the sun.

Jackson's 95 Theses - Thesis 51

Out of love for the truth and the desire to bring it to light, the following propositions are set forth.

Fifty-one: The singular relationship between Dog and Stick cannot be fully comprehended by Humans. Therefore it is Immoral for a Human to purposely and willfully interfere with a Stick when it is Contrary to the wishes of the Dog. Such acts are a Transgression of the First Order must be universally recognized as such.

A Very Unfortunate Hat

"Mother says I shouldn't talk to you."

"Your mother is right. You should go back to your table."

"She says you drink too much and you're probably a pervert."

"Where is your mother?"

"In the bathroom."

"Why don't you go join her?"

"Do you drink too much?"

"I used to. Now I drink just the right amount."

"What's a pervert?"

"A pervert is a person who enjoys something other people think he shouldn't enjoy."

"Like lima beans?"

"Lima beans?"

"Mother says we should eat lima beans even if we don't like them because they're good for us, but I do like them."

"The next time your mother serves you lima beans, you tell her you're a pervert for limas."

"Okay. That's a very red hat."

"It is, isn't it. My granddaughter gave it to me. Do you like it?"

"Well, it's very red."

"Yes, I feel the same way. Still, my granddaughter gave it to me, so I wear it."

"Is she blind?"

"Pardon?"

"My cousin Walter is blind. His mother picks out all his clothes for him because he's blind and can't see. He's twelve."

"No, my granddaughter isn't blind."

"She must be very fond of red."

"She's a pervert for the color red."

"It's a very unfortunate hat."

"Yes. Cardinal Wellman wears a red hat."

"I don't know him. Is he your friend? Does he drink too much too?"

"I don't know. Probably. Given the state of the Church these days I would, if I was him."

"Did his granddaughter give him his hat?"

"I don't think the cardinal has a granddaughter."

"Maybe he'll have one when he gets old enough."

"Maybe. I'd like to read the newspapers that day."

"I should go back to my table before mother comes out. I don't want to get scolded."

"Yes, go. I don't want to get scolded either."

"My orange juice will be getting warm. I'm a pervert for orange juice."

"Listen, kid, maybe you shouldn't use that word."

"Why?"

"Just trust me on this."

"Mother says I shouldn't trust strangers."

"Go drink your orange juice."

By the Window

What I admired most about her was the way she always sat by the window. She didn't hide from anybody. It would have been easier to hide.

I don't know what happened to her face. Traffic accident, maybe. Maybe some defective fireworks. An accident of some sort, surely. I'd hate to think somebody did that to her deliberately. Her left cheek and jaw were a mass of scars and oddly stretched, weirdly pale skin. Like the face of a porcelain doll that had been broken and badly repaired.

She'd come to the coffee shop two, three times a week. I assumed she was coming from the nearby hospital. Some sort of therapy maybe. She always sat alone, always. She kept her book in her fist and her eyes on her book. She didn't avoid eye contact, but she didn't shy away from it either.

I only knew her in a coffee shop sort of way. Which means I recognized her, but didn't know her name. I knew she liked to read science fiction, but didn't know where she worked or even

if she worked. I knew she liked a venti caramel macchioto, but didn't know if she had...or had ever had...a boyfriend, a husband, a lover.

Sometimes she'd sit at a table near me and I could smell the light fragrance she wore. Sometimes, in fact, I'd be so focused on my laptop that I wouldn't even know she was there until I smelled her perfume. The scent seemed somehow too flowery for her, in her solid-colored crewneck sweaters, her khaki pants, her sensible sneakers. Her ruined face. At first I decided the scent was probably a Christmas gift from her mother. Then I changed my mind; it was too sad. A woman should never be given perfume by her mother.

A week must have gone by before I realized I hadn't seen her recently. Two weeks, three weeks. Now I find myself sitting more often by the window, looking for her. I've started reading science fiction and drinking caramel macchiotos.

I've decided she's finished her therapy. I've decided she's got a good job doing web design. I've decided she's found another window to sit by. I've decided she's happy.

Is / Isn't / Is

Dance is my life. I hear people say that. I hear my own friends say that. It bothers me. If dance is your life, doesn't that mean you have a pretty shallow and narrowly-defined life?

Dance is

not my life. Dance is one of the things I do to enjoy life. It's an expression of my life. It's an important facet of my life. But my life is larger than dance. I have my friends and family, I have my lover, I have my cat and a parakeet and books and movies and music. I have a life outside of dance.

And yet, I can't imagine my life without dance. Dance infiltrates everything I do. It's shaped the way I walk. It affects the way I reach for the salt on the top shelf of the cupboard. It influences how I pick up my car keys when I drop them. It allows me to glide effortless through the crowds at the market. Dance makes putting on socks an act of pleasure. It guides the way I breathe. Dance pulls me the way the moon pulls the tide.

Without dance my life would be less than it is. Without dance my life would be flat. Dance is...my life.

Saturation Point

The only people in New York City who look up are the tourists. They're looking at the buildings, though, not at the sky. They don't even think about the sky. Not him; he knows the sky is up there. That's why he refuses to look up.

He looked up all the time as a boy growing up on a farm in Mississippi. Weather matters to farmers. They learn to pay attention to cloud formations, to the color of the sky, to the direction of the wind, to the humidity. They go to church and pray for good weather. He learned to see the inherent beauty of weather. He perceived a sense of dramatic inevitability, an implacable but undeniably loveliness even in the most chaotic weather systems, a deep sense of order underlying it all.

He went to college and studied meteorology. He looked at books, he looked at maps and charts, he looked at graphs of annual precipitation, he looked at doppler radar screens and computer simulations. And every day he went outside and look up at the sky.

After college he got a job as a television weatherman in Biloxi. It paid well and he was happy. It was important work, he thought, telling working folks what sort of weather to expect the next day. He didn't stay at that station long. He was a black man who could speak like a white man, he was clever and amusing, and he could read naturally off a teleprompter. Nobody was surprised when he was offered a job by a New York station.

He moved to New York. After a year or so he met and married a lawyer who was born in Jamaica. They bought a townhouse in a fashionable neighborhood in Harlem. He bought his wife a custom-made bed and in that bed they made a daughter. He looked at his family, he looked at the camera, he looked at the teleprompter and he smiled as he read the weather report. He never looked back and he stopped looking up.

His daughter was killed two months before her fifth birthday. She'd wanted to walk down to the park. While his wife fetched her hat, the child waited on the front stoop. A man walking his Rottweiler passed by and she reached out suddenly to pet the dog. The dog, startled by the motion, seized her by the upper arm. His wife, hearing the screams, rushed out. She saw the man trying to wrestle the dog away. She ran into the kitchen, called 911, and grabbed a Henkel chef's knife. Outside, her daughter had stopped screaming but the dog still refused to let go. She began to stab the dog. The dog's owner tried to stop her, so she stabbed him too. The police officers responding to her 911 call saw a woman stabbing a man, and shot her.

He was at work when it happened, explaining to visiting school children why it rained. He explained how warm air causes the water in rivers, lakes and oceans to evaporate. The water vapor rises in the air. The temperature of the air falls as you go higher. There's only so much water vapor the air can hold at any given temperature and when the water vapor exceeds that point, it begins to rain. The point at which it can't take any more is called the saturation point.

He couldn't understand why his family was dead. He tried to analyze it logically. He searched for some underlying sense of order to it. But he couldn't find it. He quit his job. He sold the townhouse. He tore apart the custom-made bed and constructed a crude cross from the bedframe.

Now he walks the streets of New York City, refusing to look up at the sky...even when it rains.

It's okay....

So here I am, man, just sitting here. Just sitting here and waiting, man. I hate waiting, I hate waiting. I'm a doer, I gotta be doing something something, all the time, man, or I get spasmed out.

Spasmed man.

But it's okay, it's okay. While I'm waiting here I can work on my novel, man. I been in a bad place on the novel, a bad place, like I know what I want to happen next, man, but it just takes so

fucking long to put down the words. I need one of them voice things, one of them things you can talk into, man, like a microphone and the computer just types the words out for you. I need one of them things, man, but they cost like a million bucks and ain't no way I'm gonna have a million bucks, man, unless I sell this novel and it gets made, like, into a movie but first I got finish writing the damned thing and I ought to work on it now while I'm waiting, but I didn't bring my computer, man, I got to remember, got to remember bring the fucking computer next time, man.

But it's okay, it's okay cause a waiting room ain't no place to be writing, man. Coffee shops, that's where you write, coffee shops. But not Starbucks, man, because Starbucks is the fucking

devil, man. I mean it, I do, cause I read this thing on the internet, man, and it was all about, like, how Starbucks owns like half the coffee beans in the world, man. Half of them, or something like that, and they exploit their workers. I don't remember if it was the guys that pick the beans or the guys in the shops, man, the ones that pour the coffee but Starbucks man, they're the devil, really. So I don't work on the novel at Starbucks, man, I don't even go there.

I gotta pee, man. I wonder how long I'm supposed to wait here. I wonder if I could leave for a bit, go get some coffee man, but not at Starbucks. But coffee makes you pee, man, pee like a racehorse. I shouldn't think about peeing, it'll just make me want to pee worse, I should think about the novel, man. I should really be thinking about her. I wouldn't even be here if it wasn't for her, man, I'd be at my crib or in a coffee shop, man, someplace I could pee whenever I wanted to.

But it's okay, it's okay. It's not her fault, man, not really not really not really. Well, it really is her fault, when you get down to it, man, when you get right fucking

down to it, but it don't make no difference. It don't make no difference cause here I am, man, here I am waiting waiting, man, with no computer and no coffee and I really really got to pee, man.

But it's okay, it's okay.

Scarred for life

"You let her wear

those?"

"That's what she wanted," he said.

"To

school? You let her wear those to school? No wonder she's crying."

"It's what she wanted. I thought that was the plan. Give her a bit more autonomy, let her make some of her own decisions."

"It never occurred to you that the other girls would tease her?"

"Well, no. They're just kids. It's not as if...."

"Six year old girls aren't kids; they're feral cubs. They hunt in packs. They seek out the the innocent, cut them out of the herd, slowly rip them limb from limb, then devour them whole."

"I didn't know. I figured she knew what she was doing."

"She's

six. Really, all you had to do was get her dressed, give her breakfast, and take her to school. Twice a week, that's all you have to do."

"I thought that's what I did."

"What you did is allow the poor child to get emotionally scarred for life."

"Oh, come on, it's not that bad. So she got teased a bit. It'll toughen her...."

"For life. She'll still remember this when she's our age. She'll remember it when we're old and she has us in a nursing home. It'll be your fault if we find ourselves being wheeled around the home wearing nothing but adult diapers and Dorothy's ruby fucking slippers."

"Don't you think you might be exaggerating just a bit?"

"Tomorrow, I want...promise me this...tomorrow, I want you to make sure she's wearing the plainest, blackest, most dull and boring shoes she's got in her closet."

"Okay."

"I want shoes so dull they'll be like an anasthetic."

"Okay."

"Shoes that will actually put other kids to sleep. I want them keeling over in the hallways."

"Dull shoes tomorrow, got it."

"I hope you at least gave her a decent breakfast."

"All she wanted was a.... Why are you looking at me like that?"

Super Wash

I work over to the Super Wash. Been there since I got laid off down at the Commings plant, October '98. Had a good job there, tool and die machinist. Made good money, too. Then they got them computers, do it a lot cheaper and do it twenty-four seven. Bunch of us got laid off.

Sometimes I think I should've stayed in the service. I was in the Army, three years. Fought in Desert Storm, 1991. I guess you'd call it fighting. I was a loader in an Abrams M1A1. You don't see much in a tank when you're fighting. Not if you're a loader. You're too busy loading. Hell, the war only lasted a hundred hours anyway. We took down a few T-55s. We got shot at. So they told me. How the hell would I know? I'd sure as hell know if we got hit, but we didn't.

It's a responsible position, being a loader. You got to be quick. You got to get the right ammo for the right job. You can't get rattled. Down at the Super Wash, they won't even let me close up the station.

Each 120mm round we fired off cost about six hundred dollars. I don't know how many rounds we fired in that hundred hours. At least five hundred. We shot the shit out of everything. I figure I spent maybe three hundred thousand dollars in the Gulf War.

You know how long it'd take me to earn three hundred thousand dollars working down to the Super Wash? About seventeen years.

We kicked the Iraqis out of Kuwait, though, sure enough. But I don't know...I think I'd rather have the three hundred thousand dollars. I'd take off these stupid Super Wash coveralls and burn 'em.

Beautiful to me

My hand knows the exact shape of her cheek. My eye knows every curved millimeter of each of her thirty-seven different smiles. My neck knows the contour of her face when I hold her close against me and feel her slowly begin to relax. My nostrils know the fresh smell of her after she showers, and the sharp smell after she's worked out. My arms know the small bones of her shoulders, my palms know the angle of her hips, my fingers know the firm clasp of her hand as we walk.

Her thin wrist is a miracle to me. Her nose is a delight to me. Her eyes are a joy to me. I would rather visit her dimple than all the natural wonders of the world.

Jackson's 95 Theses - Thesis 22

Out of love for the truth and the desire to bring it to light, the following propositions are set forth.

Twenty-two:It is Vexatious beyond all measure and an Offense in the eyes of the Great Architect for canine companions to be Subjected to the Indignity of performing Tricks in exchange for Treats. Having earned a Treat, to further require and Oblige a canine to engage in Humilitation solely for the Perverse Amusement of humankind is an outrage against Nature.

Piece of cake

Turk's looked like any other independently-owned service station. Small office with a sun-bleached spark plug calendar. Two bays with hydraulic lifts. The service area lined with old metal shelves crammed with oil-stained cartons and boxes containing carburetors, fan belts, coils of radiator hose, air filters, and quarts of Quaker State. Couple of hefty, greasy-nailed guys in coveralls shuffling around inside.

For the last nine years Turk had run a game in the back room. A friendly game on Friday nights. Sometimes the game would last until Sunday afternoon, but usually not. Turk took seven percent off the top. His taste was never less than eight hundred rarely more than fifteen and a half. There was usually fourteen, maybe fifteen thou on the table.

Not enough to attract federal heat. Maybe enough to attract local cops. More than enough to attract a couple of neighborhood mooks looking to make a score.

Put on a blue mechanic's jacket, buy an orange jumpsuit from Sears. At a signal cover your face with a stocking stolen from your girlfriend's panty drawer, step into the garage bay, pop the two hefty guys replacing a muffler. Open the door to the back room, take care of business.

In and out in five minutes, tops. Piece of cake.

Woman with a Yellow Musette Bag

I like bad weather. I like standing under an awning, watching people go by. People keep their heads down when the weather's ugly.

It gives me a chance to look at them. You can't look at people in this city. You can look

toward them, you can look

around them; you just can't look

at them.

A moment ago a young woman passed by. She was tall and must have been a dancer. Even though she was rushing to get out of the weather she moved with a dancer's confidence, sure-footed and surgical. A yellow musette bag was slung carelessly over her shoulder, the brightest yellow you can imagine on this grey day. Her head was tipped against the sleet and I couldn't see her face, but it was obvious she was beautiful. Only beautiful people move like that. Maybe it's the moving that makes them beautiful.

She passed me so closely I could smell her. She smelled like cookies. Fresh-baked cinnamon cookies. She passed so close I could have reached out and touched her cheek. Her perfect cheek. Her lightly freckled cheek.

I could have touched her. But it would have startled her, and being startled she would have lost her beauty.

Standing there under the awning, protected from the sleet, I let the woman with the yellow musette bag keep her beauty. She'd lose it soon enough.

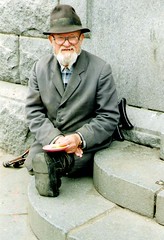

Lost it all. Almost

He lost his legs in the war. A land mine, he tells people...and in a way it's true. A land mine destroyed the lead truck of the convoy. The second truck in line swerved to avoid colliding with the first. He was a passenger in the third truck. He'd jumped out to see what was happening and was hit from behind by the fourth truck.

His teeth he lost to bad hygiene and a fondness for hard rock candy. The candy reminded him of Christmas mornings as a boy. Most of his teeth were gone, but he could still suck on the candy.

He lost his wife to cancer. After the war she'd worked for the railway, scrubbing the exterior of the cars with harsh soap and a stiff broom. On weekends she took in laundry, which he would help fold. He'd loved those weekends; they gave him something to do and the smell of freshly-washed laundry filled their small apartment.

He lost his faith in God when his wife became sick. He still

believed in God; he just didn't trust him anymore.

The use of his liver he lost to an excess of plum brandy. The Slivovitz didn't ease the loss of his wife, but it helped him to sleep. You could trust Slivovitz.

He'd learned to live without his legs, he managed to get by despite his lack of teeth, he'd come to accept the death of his wife, he didn't need God, and he didn't much care whether or not he had a functioning liver.

On Sunday mornings he'd sit on the steps of the church, toothless and legless, with a pint bottle of plum brandy in his pocket. He'd ask the parishioners to light a candle for his dead wife, and he would graciously accept their well-wishes and their coins.

Inside he'd be laughing. Laughing at the priest, laughing at the parishioners, laughing at God, laughing at himself. He hadn't lost his sense of humor.

Waiting

Photograph by lil.

Photograph by lil. They'd be patient. They were always patient. They would wait for her in the terminal, knowing she'd be annoyed if they waited by the track gate. "I'm not a child," she'd told them once. "You don't have to hover by the gate waiting for me."

So they would wait in the terminal, standing there with a bovine patience that would also annoy her. She'd suggested they wait for her at home, that she'd get there just fine. But it was important to them that they be there to meet her. It was important to them to make the effort, to get themselves ready and travel to the station and wait for their daughter to arrive. It was important to them, and because it was important she couldn't bring herself to insist they stay home.

During the visit they'd struggle to find things to talk about. Her mother would prepare the meals that had been her favorites fifteen years earlier. Her father would ask about the maintenance of her car. She'd learn which of her high school friends had recently had another baby. Nobody would mention politics or religion, and her parents would very carefully avoid asking her if she was dating anybody or why she wasn't married.

When the visit was over, they would get themselves ready and travel to the station and wait for their daughter to leave again. They'd wait in the terminal, mute with love, while their daughter wandered off to find her train.